There is A Light That Never Goes Out

I was fifteen years old when Meagan was born.

At the time, she was just another cousin, one of ten (plus a niece and two nephews) who came one after the other, in rapid succession, over a few short years. Several more cousins followed later, but the mid-1980’s was our family’s baby boom. Meagan, another cousin, and my first niece were born just months apart in 1984-85.

My mother was the oldest of four girls by eleven years, so I was twelve when the first cousin made her entrance. I went from two brothers to a whole lot of little girls (and a couple of boys) in an instant. I loved it. I loved them all. Every single one of them.

Family get-togethers took place at my grandparents’ home in Indianapolis. Thanksgiving, Christmas, Mother’s Day, Indy 500 Day… upwards of 40-50 people would show up to celebrate, eat, and just be together.

Family. A wonderful, loving, huge family.

My mother was the only daughter to leave Indianapolis. She, my father, and my eldest brother moved to Michigan, just before I was born. My big family lived close to each other, something I never had. When other kids went to Florida on spring break, we went to Indianapolis. And I loved it. I couldn’t get enough of my aunts and uncles and brother and sister-in-law and nieces and nephews. And cousins. So many cousins. I reveled in every year of their lives and loved watching them grow into individuals.

They talked to me. They told me things they couldn’t/wouldn’t tell their parents. I was the cool older cousin who they could confide in and would call them on their shit when they were being idiots.

I thought of them more as nieces and nephews than cousins, because I was so much older. I still do.

I used to stay with Meagan’s parents, my aunt and uncle, on their property south of Indianapolis. They let me smoke. They were cool. Their kids were cool. he rest of my family was cool in their own ways, but this family and I jibed, really well. They’re my speed. They got me.

The children had the run of a forest, and took full advantage. Meagan had the spark of adventure from early on, a pure blend of her older sister and brother. She was her own person.

When I graduated from college, I moved from Michigan to Georgia, and only saw my family once or twice a year. Meagan actually came to visit me once there (mostly for a place to stay while she and her friend went to some concerts).

She was nineteen.

Twelve years after I left Michigan, I moved to Los Angeles, and saw them even less. And then, in 2010, my young family and I moved to British Columbia.

The last time I went home to Indianapolis was April of 2009. Meagan wasn’t there; she had moved to Austin, TX.

We’re planning a trip home in August for a family reunion. I had hoped she and her husband would make the trip as well.

A curious thing about my family: my mother moved away from the homestead, but my two brothers moved back (one a couple of hours away, but still Indiana). Everyone else stayed close. Except four of us. One child from each sister’s family moved away: me, a cousin who moved to LA before I did, a cousin who is now in Pennsylvania, and Meagan, who went from Austin to Seattle.

Over the years, I’ve seen a few family members who have ventured West. Mostly those coming out to visit Meagan or my oldest nephew, who had also moved to Seattle around the same time we came north.

Two years ago, I took my four boys down just across the border into Washington, for a picnic at my (second) cousin’s house. Meagan would be there with her mom and stepdad, my aunt and uncle, who had come to visit.

I was beside myself. It had been seven years since I’d seen any of them, and I was craving family time in a desperate way.

I pulled into the drive, and barely got the door open before Meagan was dragging me out of the van, yelling “WENDY! I LOVE YOU!!” She gave me one of the biggest hugs of my life. It felt like home.

My cousins and I all look pretty much alike. It’s obvious we’re related. My aunt looks like my mother, who passed in 2000. Sitting there with them, I was home, if only for an afternoon.

Over the following months, Meagan and I talked more, and, last summer, we finally got a chance to hang out and talk and just be together for a few hours.

Home.

She took me to her restaurant and proudly announced to anyone who would listen, “this is WENDY!! She’s my COUSIN!!”

She also picked up my son from SeaTac when I couldn’t get down from Vancouver in time.

“How will I know who she is, Mama?”

“She looks like me, baby. You’ll know her.”

And he did.

The three of us went to her restaurant for lunch and laughed and ate too much. I hated leaving.

I texted with her a lot, mostly about when/if we could actually get together. A lot of “I love you’s” on both ends.

If Meagan loved you, you knew it. You felt it down into your soul.

A few weeks ago, my nephew got married in Seattle. My husband and I got a sitter and went down for the weekend alone. I was beside myself with excitement, for so many reasons. I was finally getting to meet my two-year-old grand nephew for the very first time. I was finally getting to see my niece for the first time since 2009. I was seeing my big brother and sister (in-law only as a technicality), her mother, and my younger nephew again. And, I was finally going to meet Meagan’s husband of nine years, Nik.

The weekend did not disappoint.

Friday night we had no plans and the others were getting ready for the morning wedding, so we met up with Meagan for drinks.

Sitting at the busy bar where Nik works (trying to figure out which employee was him), David asked about her. He hadn’t seen her since probably 2006 and didn’t really remember her all that well.

“You’ll know her. She looks like me.”

And he did.

“WENDY!!!” came booming through the bar.

“MEAGGIE MAY!!” I boomed back.

To her husband: “See, she called me Meaggie May! She’s family!”

Nik knew who I was, too.

Meagan and I look so much alike.

We drank and laughed and were loud.

We moved on to the next bar, a Buffalo Wild Wings. The place was pretty empty, but the booze flowed and that was good with us.

We talked about restaurants. Both of us finished college, got real jobs, and quit them in favour of working in bars.

We talked about life. We talked about family.

So much about family. We laughed about her and her siblings as children and my adventures with her parents. We cried about losing my mom. We shared silly stories about our lives together. And we sang songs. Loudly.

Everything we did that night was loud.

I could be loud with Meagan. She got me.

Out of all of my cousins, Meagan got me. We were kindred spirits with no fucks to give.

She accepted me for my loud and crazy and emotional self. It was easy – Meagan, too, was loud and crazy and emotional.

Two peas in a pod.

We sat together at the wedding, had drinks together between the ceremony and brunch, then drank more together at the “after party” that night in Seattle.

When the party was over, we all moved elsewhere. She knew where to go; she knew the people working there.

She was me when I lived in Atlanta, hooked in to the bar scene. I relived a little bit of my rowdy youth (my early 30’s) through her.

The next day we were supposed to meet up again. I had a box of canned goods in my car for them. I can everything in sight; it’s one of the things I love to do nowadays. Every chance I get, I take them food. I feed them. I brought a ton of stuff that weekend.

We got caught up visiting with my brother’s family (and my sweet grand-baby), then had to get home to relieve the sitter. We missed seeing Nik and Meagan one last time.

I’ve been texting with her for a couple of weeks now, trying to figure out where we could meet so I could get the jars to her. We finally decided to meet up in the middle – the beach at Deception Pass – so we could spend the day playing with the kids instead of just handing off a box of canned goods in the parking lot of Target.

The box is still in my van.

Her last text is still on my phone.

She’s gone.

Three days ago (has it been that long?) Meagan passed away suddenly.

We still don’t know why.

But it doesn’t matter.

She’s gone.

She was 33.

The beautiful girl whose diapers I changed when she was a baby, and played with as she grew. The beautiful woman who had become not just family, but my friend.

She was my friend.

She got me.

She loved me.

Meagan had a smile that absolutely radiated. A lot of people say that about smiles, but Meagan’s smile was bigger than life.

She was alive on a level most people only wish for.

She was vibrantly present, and when she was near, you knew it. She focused on people like a laser beam. Her joy of life and love for everyone in it was palpable.

The loss of her is palpable.

The pain is unbearable.

The hole in the world is cavernous.

But I will gather myself together, take the love she gave me, and put it out into the world.

Meagan was the brightest light, and she will shine on through everyone she loved and who loved her.

And every time I see her picture, I will smile.

And be loud.

**********************

Meagan was the breadwinner in her family while Nik finished college. Her coworkers have started a GoFundMe to help him get though this difficult time. If you’d like to contribute, here is the link.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read MoreBe The Village

Autism parents. Autistic adults.

Two communities that have the same essential goals, but are rarely able to meet on common ground.

One point of contention is the internet, and how autistic people are portrayed.

The latest flame on that fire is a video by Kate Swenson of Finding Cooper’s Voice, wherein she talks about her son Cooper’s nonverbal autism.

Kate’s website, Finding Cooper’s Voice, rose in visibility last year, when her video about an altercation at a special needs playground went viral. Then, in October, Kate and Cooper’s video submission to Jimmy Fallon and Today’s “Everything is Mama” contest took the top prize.

Kate makes a lot of videos about her family, and Cooper, in particular.

Kate’s latest video

This latest video, posted via Today.com, as caught a lot of attention, both good and bad. Parents of nonverbal children understand and sympathize, and a lot of autistic people are very, very upset.

The main concerns I’ve seen are that the video is “ableist,” “exploitative,” and essentially a Mommy Blog pity party.

And they’re right, to a point.

People have been arguing since the invention of the internet whether or not posting videos/photos of their children is acceptable. Some think it’s absolutely abhorrent, while others embrace the platform with abandon.

There is a lot of concern about Cooper’s right to privacy, and future humiliation he may suffer because of his mother’s posts and videos. I, myself, have faced similar scrutiny, particularly when I started this site, eight years ago. I take care not to post anything that disrespects or would embarrass my children, and from what I’ve seen of Kate’s work, she does the same.

My opinion. Yours may vary.

I think the situation here is a little more serious than whether or not Kate is indulging in self-pity at Cooper’s expense.

This is also about more than Cooper’s right to privacy.

This is about his life.

People like to say that special needs parents are “picked” for their children, or that “God never gives them more than they can handle.”

Those are nice tropes, but in reality, parents of special needs children are no different or better or more special than any other parent. Every parent wants the best for their child, and sometimes that journey is a lot harder and full of stress.

A kind of stress you can’t explain to someone not in it.

Even another autistic person.

I am autistic, and I am also a parent. A parent with four children, three of whom have special diagnoses, two of whom are on the spectrum, too.

I understand that to an autistic person, hearing a parent say “horrible things” about their autistic child is “ableist” and offensive.

I also understand, as a parent to autistic children, that hearing a parent describe their reality is hard to hear, but necessary.

This is a cry for help. For her, for her child.

Instead of vilifying her, let’s recognize that and be her village.

Kelly Stapleton was an integral part of the autism blogosphere. She was a bright and shining light, while simultaneously sharing her struggles with her daughter Izzy.

Her life was hard. Really, really hard. And when Kelli thought she had nowhere left to turn, and nobody left to help her family, she made a desperate decision that changed her family’s lives forever.

She tried to kill Izzy, and herself.

Kelli and Izzy

Kelli got to the point where that action seemed like a logical ending to their pain. To her pain.

I am in no way condoning her actions. Not at all.

However, I think we need to learn from them. There has been an epidemic of caregivers taking the lives of their autistic children/wards, most because they can’t find a way out of their world.

The autism world can be one of utter isolation. Family and friends back off; total strangers judge silently.

As autistic adults, we purport to want the very best for our fellow autistics of all ages. It’s time to put some walk to that talk. It’s time to reach across the table with an olive branch and a life jacket.

We simply cannot have it both ways. If we do not reach out and support parents who are desperate and in pain, they may break. Supporting these parents, instead of ridiculing and criticizing them, IS supporting autistic people.

How can we possibly insist on putting the health and welfare of autistic people first, if we are not willing to help their caregivers?

We know best. We are their children, grown up. We know what our parents went through, and it wasn’t always easy. Would you have wished them to suffer in silence, or to reach out for a hand to hold or shoulder to cry on or simply a sympathetic ear?

We can do better. For Cooper. For Izzy. For every autistic child. They need our village.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read MoreFacing Our Fears

I’ve been away for a bit. I’ve been in a self-made cocoon of sorts, waiting for the right time to reveal my “new” self.

Or the self I’ve always been, but didn’t really know it.

Anyway, I’ve been thinking on the best way to start the conversation here. This place that I’ve built to laugh and cry, and bemoan, and celebrate autism in our family. This place that has become a safe haven for me and others, a place where it’s OK to be our true selves, autism, warts, and all.

I thought for a while that I needed to bring platitudes and great revelations. That I needed to be profound.

And as I sat, cozy and safe in my self-imposed little box, it came to me.

Rather, Jack came to me.

Jack has been my teacher on so many levels, and I should have known this would be no different.

A couple of weeks ago, we went to a small amusement park and a big water slide park on the same day. We don’t do amusement parks, as a rule, for a few different reasons: Money, crowds, autism, crowds, crazy children, lines, money, and, of course, crowds. The kids have been on a few rides here and there (most recently the Great Wheel in Seattle), but we haven’t done a full-fledged amusement park since Disneyland years ago when the kids were small.

The only water slides my kids have encountered have been the small ones at a downtown spray park, and the slide at our local pool (not small by any means, but not theme-park-sized).

I was worried how Jack would do on the rides, since he really seemed to hate them when he was younger. I also didn’t know how he would react to the water-slides, as you can’t exactly avoid being splashed in the face or dunked underwater.

To our relief, the amusement park was both quite small and fairly empty. The kids didn’t have to wait in line for anything. It was like an Autism Miracle.

He handled it all. Really well. By himself.

For instance, he did this:

He both shot his brother in the face, and took many hits in return. All with a big grin.

This one amazed me. Jack HATED swings as a baby and small child. It took about two full years of occupational therapy to get him to not only ride a swing, but enjoy it. Now he’s a swinging fool.

He did this:

This ride made my husband ill just looking at it. They’re up there spinning around, while spinning around. Like teacups up in the air.

And then he did this:

If you can’t tell from the photos, this little ride here is like a carousel on acid. You sit on a horse, and the platform starts to rotate. Then, the whole thing rises up one side of an arc, then down and up the other side. All while the platform is still rotating. Like someone thought the pirate ship that goes back and forth is a little too tame, and the carousel is just not dangerous enough.

So yeah, he rode that thing. Smiling.

We headed to the water slides, and Jack took off alone. I was worried about him, but figured he’d end up entertaining himself in the splash areas or pools.

Toward the end of our visit, my child ran up to me, dripping wet.

He had done this:

FIVE TIMES.

He was so excited to tell me. “Mom! I really conquered my fears today!”

And then he ran off to do it again.

I realize now that I haven’t been hiding in contemplation so much as in fear. I’ve been afraid. This post changes everything for me, but it’s time. If my child, who has come so very far in his almost-nine years of life, can stand up to his own fears and break through to the brighter side, so can I. And I will, for him.

This is my vertical drop.

So, here goes.

My name is Wendy, and I have Asperger’s.

I am autistic.

And I am happy.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read More

Canucks Autism Network Sports Day Adventure!

As much as I complain about the state of autism support here in the Lower Mainland, we also have some pretty cool things going on. There are several societies that provide access to camps, supports, and many other activities for autistic individuals.

One group here doing it really right is the Canucks Autism Network (CAN). They help keep autistic kids involved in sports and a lot of other social events. CAN usually tries to involve siblings as well, to help foster a whole family experience. We absolutely love them.

Jack and I were very excited to attend the CAN 2nd Annual Sports Day on May 18th at BC Place. It was a day of serious fun with representatives from the Vancouver Canucks, the Vancouver Whitecaps FC, the BC Lions, and the Vancouver Canadians. I could tell you all about it, but I’d rather show you. Enjoy!

We arrived a bit early, so it was a good hour before the event started. CAN had set up face painting and colouring, but the waiting still got old after a bit. Anticipation and autism don’t mix well. The CAN volunteers are seasoned, though, and did their very best to keep everyone intact.

As everyone was introduced, we got a cool view of everything from above.

The kids were divided into four groups, and each group spent twenty-five minutes with an activity, then rotated to the next one. Jack’s group had hockey first!

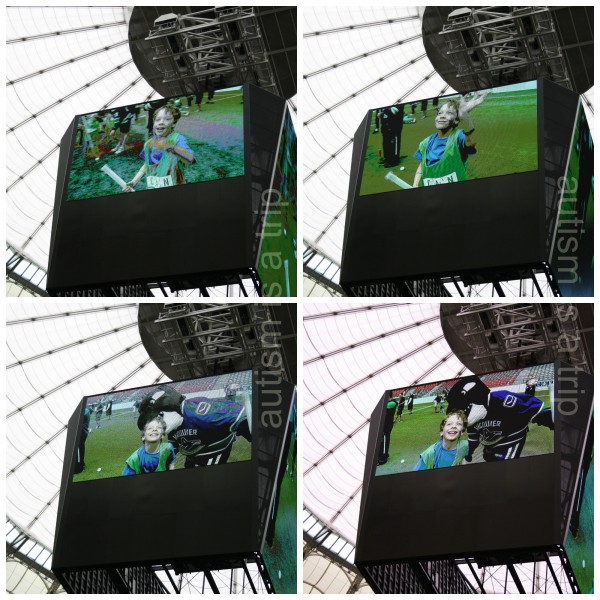

There were photographers and cameras capturing it all, and showing everyone on the jumbotron. Jack noticed it quickly, and played right to the camera. That’s my boy.

Fin, the Canucks mascot, had a great time with the kids. He has a thing about chewing on their heads, though. They should keep an eye on that.

Next up was football, and Jack learned how to run the ball, throw the ball, and do a wicked touchdown dance.

We moved on to soccer, and Jack put the Whitecaps guys through their paces. A lot of the other kids were ready for a break, but Jack kept on going. And going. And going.

Finally, we moved over to baseball. After some pointers from Mama, Jack smacked a few line drives.

Canucks announcer Ed Murdoch closed out the event.

We had a lot of fun. Thank you CAN, for everything you do!

*************************************************************************8

Click HERE if you’re interested in joining CAN.

Click HERE if you’d like to be a CAN volunteer.

Click HERE for information on how to donate to and fundraise for CAN.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read More

Autism in British Columbia: Crisis in Process

My son Jack was born in the United States and raised in Los Angeles until the age of four and a half. Just before he turned two, he entered the California Early Start program for children with a risk of developmental delay or disability. We called for an appointment in August of 2o06, and by the end of September of the same year, he was enrolled in a variety of interventions and therapies.

At age three, he was formally assessed and diagnosed with autism by both the Lanterman Regional Center and the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). He was transferred to autism-specific supports, where he remained until we moved.

From the time Jack was twenty-two months until he was four and a half, Jack received the following interventions and therapies:

AGE TWO

- Collaborative preschool with typical peers in a clinic-based classroom, three-to-four days a week

- Two hours a week of clinic-based Occupational Therapy

- Two hours a week of home-based Speech Therapy

- Several sessions of Feeding Therapy

- He was also offered full-time preschool, additional Occupational Therapy, Floortime Therapy, and Respite Care, which we did not feel were necessary at the time.

AGE THREE to FOUR

Provided by LAUSD:

- Individualized Education Program (IEP) support

- Collaborative preschool with typical peers in a public school classroom, five days a week

- Full-time Behavioural Intervention Implementation (BII) aide at school

- Two half-hours a week of school-based Speech Therapy

- Two half-hours a week of school-based Occupational Therapy

Provided by Lanterman Regional Centre:

- One hour a week of clinic-based Occupational Therapy

- Twelve hours a week of home-based Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA)

- Respite Care

- Parent training workshops

We also supplemented his therapies at home, with strategies learned from his providers.

Several of the supports at school and at home were coordinated through the same non-profit organization, so there was continuity in both areas. We felt very confident that our son was receiving every support he needed, and that should he need more, the options were available to us.

We were given choices of providers and schedules, and the ability to change supports and therapies as we saw fit, but we were guided through the process by a social worker at Lanterman (Early Start), and then a caseworker at Lanterman, a support worker at LAUSD, and a coordinator at the non-profit who provided our BII and ABA aides.

It is important to note a couple of things. First, we never saw a bill. Not once. My husband and I signed authorization forms, reports, and time cards, but we were never financially responsible for anything.

Secondly, we were given suggestions and options as to what Jack needed, according to several observations and reports. We were able to give our input, but we were not responsible for creating his treatment plans. We never felt like the burden of figuring out what he required was on us.

Finally, we never saw a pediatrician or medical doctor (other than the diagnosing psychiatrists) for Jack’s autism. In fact, it came as a bit of a surprise to his pediatricians when we told them about his diagnosis. Jack has never had any of the health issues commonly associated with autism, and as it is not required in California, we had no reason to include his doctors in the diagnosing process.

When our family moved to Canada, Jack was in the process of transitioning from preschool to Kindergarten. In Los Angeles, he would have had full-time BII support, and continued with both speech therapy and home-based ABA (he had graduated from clinic-based occupational therapy) for as long as necessary.

I cannot speak to how his support would have waxed or waned over the school years, but I have only good things to say about our experiences up to that point.

I can, however, tell you what happens here in British Columbia.

Once we were settled, we were required to get Jack a new autism diagnosis from a Canadian doctor in order to qualify for provincial autism funding. Government funding is Canada’s answer to autism support, similar to the Regional Center system in California.

First, we had to see a pediatrician, and convince him Jack needed a referral for diagnosis. I was honestly shocked when he balked at giving it to us, even though Jack had already been formally diagnosed in the United States. Twice. The doctor wanted to rule out ADHD (which, it turns out, Jack does have), and Fragile X Syndrome (which he does not), before he would even consider referral. I pushed, though, and he relented.

Next came The Wait. We were told the wait time for assessment would be almost two years, and indeed it was fourteen months before he was seen.

Fourteen months is forever in the life of an autistic child and their family.

It can also be the difference between full- and no-support.

Children assessed with a spectrum disorder in BC under the age of six receive $22,000 a year of funding to pay for their various supports. The family is responsible for deciding which therapies and interventions are necessary, and all of the hows and whens and whos of making them happen. I know how overwhelmed we were in Los Angeles, and we had several agencies overseeing and coordinating everything for us.

Many families in BC are lost and confused as to what is necessary and when, and who to trust to give them good advice. They are expected to become autism experts overnight, and to know what their child needs at any given time.

Once a child on the spectrum reaches age six, the yearly funding drops to a mere $6,000. To cover every single thing the child or young adult needs.

$6,000 doesn’t go very far, in case you’re wondering.

Now consider the child who has been waitlisted until they are six or seven, eight, or older. Those children don’t get retroactive funding; they’re given the same $6,000 every other child over six gets.

$6,000 to sink or swim.

My husband and I often wonder where Jack would be in his development if he hadn’t had such intensive interventions and instead had to wait years to be seen. The difference between the two months it took in Los Angeles and the fourteen months it took in British Columbia is monumental.

It’s a lifetime.

In the first fourteen months of Jack’s therapies, he learned to use his upper body. He learned how to play.

He learned how to talk.

I cannot stress enough how important the first year of Jack’s interventions was in shaping the person he is today. That time was invaluable to him, and to us.

I have met many families of autistic individuals here in BC and have heard a lot of stories. Some wonderful, many concerning. Some downright terrible.

In the Lower Mainland, where we live, there is only one team that assesses and diagnoses autism. One team for a large and rapidly growing population – the fastest growing region in Canada.

Wait times to be seen are so outrageous, families who are financially able resort to paying for their own assessments out of pocket. Even those clinics now have tremendous wait times.

Yes, there are legitimate circumstances where a child may be older before he or she is diagnosed, but for families seeking help for younger children, the situation here can be bleak.

I cannot imagine where Jack would be today without the solid start he got at a very young age.

I cannot imagine the kind of support he would have gotten if we had to decide his plan of action alone, without professional guidance.

I cannot imagine the outcome if we had had serious budget restraints, or had to turn down therapies because we simply could not afford them.

Autistic children in Alberta get up to $60,000 a year for supports through age 18. Why should children in British Columbia not get the same?

Why do children over the age of six get so much less than younger children? Is autism less severe over the age of six?

Why are families left to fend for themselves in a province so well known for caring for its citizens?

It breaks my heart to see even one child go without the therapy and intervention he or she desperately needs. I don’t understand how a province can willingly stifle the potential of certain individuals because of their age or where they live.

It’s just not right.

It’s not Canadian.

It needs to change.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read More