Be The Village

Autism parents. Autistic adults.

Two communities that have the same essential goals, but are rarely able to meet on common ground.

One point of contention is the internet, and how autistic people are portrayed.

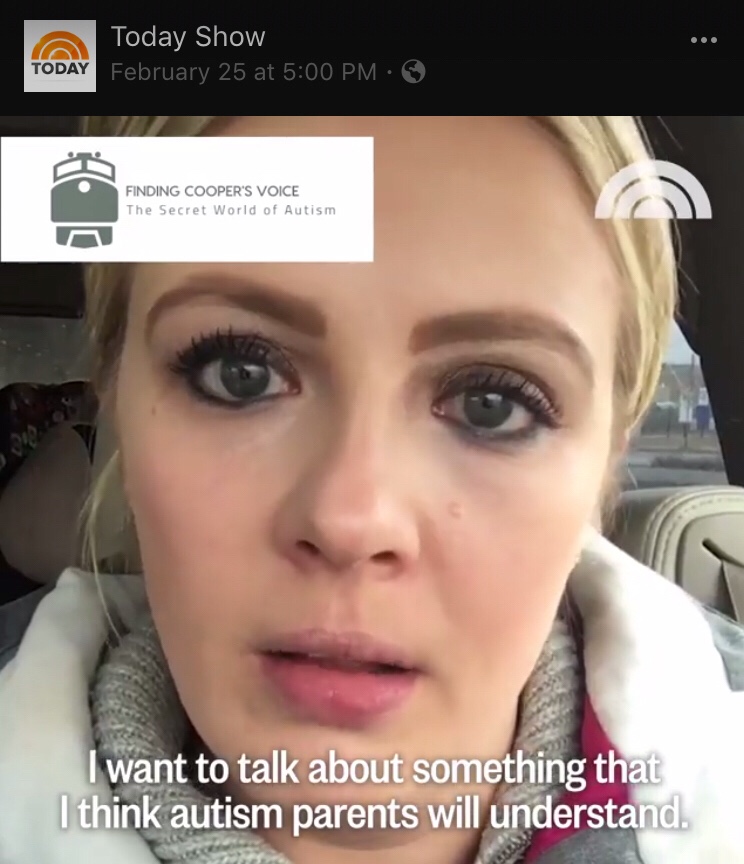

The latest flame on that fire is a video by Kate Swenson of Finding Cooper’s Voice, wherein she talks about her son Cooper’s nonverbal autism.

Kate’s website, Finding Cooper’s Voice, rose in visibility last year, when her video about an altercation at a special needs playground went viral. Then, in October, Kate and Cooper’s video submission to Jimmy Fallon and Today’s “Everything is Mama” contest took the top prize.

Kate makes a lot of videos about her family, and Cooper, in particular.

Kate’s latest video

This latest video, posted via Today.com, as caught a lot of attention, both good and bad. Parents of nonverbal children understand and sympathize, and a lot of autistic people are very, very upset.

The main concerns I’ve seen are that the video is “ableist,” “exploitative,” and essentially a Mommy Blog pity party.

And they’re right, to a point.

People have been arguing since the invention of the internet whether or not posting videos/photos of their children is acceptable. Some think it’s absolutely abhorrent, while others embrace the platform with abandon.

There is a lot of concern about Cooper’s right to privacy, and future humiliation he may suffer because of his mother’s posts and videos. I, myself, have faced similar scrutiny, particularly when I started this site, eight years ago. I take care not to post anything that disrespects or would embarrass my children, and from what I’ve seen of Kate’s work, she does the same.

My opinion. Yours may vary.

I think the situation here is a little more serious than whether or not Kate is indulging in self-pity at Cooper’s expense.

This is also about more than Cooper’s right to privacy.

This is about his life.

People like to say that special needs parents are “picked” for their children, or that “God never gives them more than they can handle.”

Those are nice tropes, but in reality, parents of special needs children are no different or better or more special than any other parent. Every parent wants the best for their child, and sometimes that journey is a lot harder and full of stress.

A kind of stress you can’t explain to someone not in it.

Even another autistic person.

I am autistic, and I am also a parent. A parent with four children, three of whom have special diagnoses, two of whom are on the spectrum, too.

I understand that to an autistic person, hearing a parent say “horrible things” about their autistic child is “ableist” and offensive.

I also understand, as a parent to autistic children, that hearing a parent describe their reality is hard to hear, but necessary.

This is a cry for help. For her, for her child.

Instead of vilifying her, let’s recognize that and be her village.

Kelly Stapleton was an integral part of the autism blogosphere. She was a bright and shining light, while simultaneously sharing her struggles with her daughter Izzy.

Her life was hard. Really, really hard. And when Kelli thought she had nowhere left to turn, and nobody left to help her family, she made a desperate decision that changed her family’s lives forever.

She tried to kill Izzy, and herself.

Kelli and Izzy

Kelli got to the point where that action seemed like a logical ending to their pain. To her pain.

I am in no way condoning her actions. Not at all.

However, I think we need to learn from them. There has been an epidemic of caregivers taking the lives of their autistic children/wards, most because they can’t find a way out of their world.

The autism world can be one of utter isolation. Family and friends back off; total strangers judge silently.

As autistic adults, we purport to want the very best for our fellow autistics of all ages. It’s time to put some walk to that talk. It’s time to reach across the table with an olive branch and a life jacket.

We simply cannot have it both ways. If we do not reach out and support parents who are desperate and in pain, they may break. Supporting these parents, instead of ridiculing and criticizing them, IS supporting autistic people.

How can we possibly insist on putting the health and welfare of autistic people first, if we are not willing to help their caregivers?

We know best. We are their children, grown up. We know what our parents went through, and it wasn’t always easy. Would you have wished them to suffer in silence, or to reach out for a hand to hold or shoulder to cry on or simply a sympathetic ear?

We can do better. For Cooper. For Izzy. For every autistic child. They need our village.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read MoreAutism in British Columbia: Crisis in Process

My son Jack was born in the United States and raised in Los Angeles until the age of four and a half. Just before he turned two, he entered the California Early Start program for children with a risk of developmental delay or disability. We called for an appointment in August of 2o06, and by the end of September of the same year, he was enrolled in a variety of interventions and therapies.

At age three, he was formally assessed and diagnosed with autism by both the Lanterman Regional Center and the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). He was transferred to autism-specific supports, where he remained until we moved.

From the time Jack was twenty-two months until he was four and a half, Jack received the following interventions and therapies:

AGE TWO

- Collaborative preschool with typical peers in a clinic-based classroom, three-to-four days a week

- Two hours a week of clinic-based Occupational Therapy

- Two hours a week of home-based Speech Therapy

- Several sessions of Feeding Therapy

- He was also offered full-time preschool, additional Occupational Therapy, Floortime Therapy, and Respite Care, which we did not feel were necessary at the time.

AGE THREE to FOUR

Provided by LAUSD:

- Individualized Education Program (IEP) support

- Collaborative preschool with typical peers in a public school classroom, five days a week

- Full-time Behavioural Intervention Implementation (BII) aide at school

- Two half-hours a week of school-based Speech Therapy

- Two half-hours a week of school-based Occupational Therapy

Provided by Lanterman Regional Centre:

- One hour a week of clinic-based Occupational Therapy

- Twelve hours a week of home-based Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA)

- Respite Care

- Parent training workshops

We also supplemented his therapies at home, with strategies learned from his providers.

Several of the supports at school and at home were coordinated through the same non-profit organization, so there was continuity in both areas. We felt very confident that our son was receiving every support he needed, and that should he need more, the options were available to us.

We were given choices of providers and schedules, and the ability to change supports and therapies as we saw fit, but we were guided through the process by a social worker at Lanterman (Early Start), and then a caseworker at Lanterman, a support worker at LAUSD, and a coordinator at the non-profit who provided our BII and ABA aides.

It is important to note a couple of things. First, we never saw a bill. Not once. My husband and I signed authorization forms, reports, and time cards, but we were never financially responsible for anything.

Secondly, we were given suggestions and options as to what Jack needed, according to several observations and reports. We were able to give our input, but we were not responsible for creating his treatment plans. We never felt like the burden of figuring out what he required was on us.

Finally, we never saw a pediatrician or medical doctor (other than the diagnosing psychiatrists) for Jack’s autism. In fact, it came as a bit of a surprise to his pediatricians when we told them about his diagnosis. Jack has never had any of the health issues commonly associated with autism, and as it is not required in California, we had no reason to include his doctors in the diagnosing process.

When our family moved to Canada, Jack was in the process of transitioning from preschool to Kindergarten. In Los Angeles, he would have had full-time BII support, and continued with both speech therapy and home-based ABA (he had graduated from clinic-based occupational therapy) for as long as necessary.

I cannot speak to how his support would have waxed or waned over the school years, but I have only good things to say about our experiences up to that point.

I can, however, tell you what happens here in British Columbia.

Once we were settled, we were required to get Jack a new autism diagnosis from a Canadian doctor in order to qualify for provincial autism funding. Government funding is Canada’s answer to autism support, similar to the Regional Center system in California.

First, we had to see a pediatrician, and convince him Jack needed a referral for diagnosis. I was honestly shocked when he balked at giving it to us, even though Jack had already been formally diagnosed in the United States. Twice. The doctor wanted to rule out ADHD (which, it turns out, Jack does have), and Fragile X Syndrome (which he does not), before he would even consider referral. I pushed, though, and he relented.

Next came The Wait. We were told the wait time for assessment would be almost two years, and indeed it was fourteen months before he was seen.

Fourteen months is forever in the life of an autistic child and their family.

It can also be the difference between full- and no-support.

Children assessed with a spectrum disorder in BC under the age of six receive $22,000 a year of funding to pay for their various supports. The family is responsible for deciding which therapies and interventions are necessary, and all of the hows and whens and whos of making them happen. I know how overwhelmed we were in Los Angeles, and we had several agencies overseeing and coordinating everything for us.

Many families in BC are lost and confused as to what is necessary and when, and who to trust to give them good advice. They are expected to become autism experts overnight, and to know what their child needs at any given time.

Once a child on the spectrum reaches age six, the yearly funding drops to a mere $6,000. To cover every single thing the child or young adult needs.

$6,000 doesn’t go very far, in case you’re wondering.

Now consider the child who has been waitlisted until they are six or seven, eight, or older. Those children don’t get retroactive funding; they’re given the same $6,000 every other child over six gets.

$6,000 to sink or swim.

My husband and I often wonder where Jack would be in his development if he hadn’t had such intensive interventions and instead had to wait years to be seen. The difference between the two months it took in Los Angeles and the fourteen months it took in British Columbia is monumental.

It’s a lifetime.

In the first fourteen months of Jack’s therapies, he learned to use his upper body. He learned how to play.

He learned how to talk.

I cannot stress enough how important the first year of Jack’s interventions was in shaping the person he is today. That time was invaluable to him, and to us.

I have met many families of autistic individuals here in BC and have heard a lot of stories. Some wonderful, many concerning. Some downright terrible.

In the Lower Mainland, where we live, there is only one team that assesses and diagnoses autism. One team for a large and rapidly growing population – the fastest growing region in Canada.

Wait times to be seen are so outrageous, families who are financially able resort to paying for their own assessments out of pocket. Even those clinics now have tremendous wait times.

Yes, there are legitimate circumstances where a child may be older before he or she is diagnosed, but for families seeking help for younger children, the situation here can be bleak.

I cannot imagine where Jack would be today without the solid start he got at a very young age.

I cannot imagine the kind of support he would have gotten if we had to decide his plan of action alone, without professional guidance.

I cannot imagine the outcome if we had had serious budget restraints, or had to turn down therapies because we simply could not afford them.

Autistic children in Alberta get up to $60,000 a year for supports through age 18. Why should children in British Columbia not get the same?

Why do children over the age of six get so much less than younger children? Is autism less severe over the age of six?

Why are families left to fend for themselves in a province so well known for caring for its citizens?

It breaks my heart to see even one child go without the therapy and intervention he or she desperately needs. I don’t understand how a province can willingly stifle the potential of certain individuals because of their age or where they live.

It’s just not right.

It’s not Canadian.

It needs to change.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read MoreA Tragedy in BC – Failing The Caregivers

Autism Awareness (ought to be Acceptance) Month is winding down, and unlike April, it will not go out like a lamb. The lion of autism injustice is still roaring, louder than ever.

While people are walking and gathering and fundraising and celebrating the wonders and gifts of autism (which I wholeheartedly support), the dark underbelly is growing. It’s time for us to face it.

Death has become altogether too common in the autism community. Every week or so there’s another story about an individual who has bolted or wandered and not made it home. And every month or so, an autistic individual is harmed or murdered by a caregiver.

The tragedies are too numerous to count, and happening much too often. They are also hitting closer to home – both in proximity and emotion.

Our children are in danger.

Issy Stapleton. Alex Spourdalakis. And now, Robert Robinson.

Last week, British Columbia resident Angie Robinson murdered her 16-year-old autistic son, then took her own life.

It’s easy to automatically blame Angie. How could a mother possibly take the life of her own child? What kind of parent does that?

A desperate parent. A parent who has reached the end of their resources, both physically and mentally. A parent who believes they have absolutely no other answer.

Nobody thinks they could ever get to the point where suicide and murder are a viable option. We all assume if things get dark enough, someone will appear with a light.

No parent, even a parent of a profoundly disabled or autistic child, wants death (I’m assuming the best, of course). Even at the very end of the rope, we are still hanging on, holding out for a glimpse of hope.

But occasionally, the darkness consumes everything, and no light can get through. There is no hope. Or, at least, that’s what a desperate parent believes.

Yes, the violent acts visited on children by their own parents and caregivers is atrocious and unimaginable. No child should ever fear for his or her life in their own home. I am not suggesting that what Kelly or Angie or Alex’s grandmother did are acceptable in any way.

But I do understand them. And I can understand how things could get so desperate for them that they felt they only had one solution.

It all comes down to support. The proverbial village. The village that supports the child needs to support the caregivers and parents, too, and therein lies the rub.

Autism supports vary from country to country, province to provice. There is no standard of practice or care even within a the US or Canada. Children and individuals with autism often need intense, one on one care, either in the home or a residential facility. Not every family is equipped to handle these situations, yet there is often little in the way of respite and support for them.

As far as I can tell, support for caregivers is pretty much nonexistent. If a family member requires placement or full-time care and none is available, what is the caregiver to do? Between a lack of professional support and the overwhelming costs of respite and residential care, it should really be no surprise that parents are losing hope.

There are two victims in these crimes. Two lives lost. Two stories that didn’t have to end this way.

When a desperate parent decides to kill their child and themselves as a way out, the entire autism community has failed.

We have failed the child by not giving them everything they need to live a happy life to best of their ability.

We have also failed the caregiver by not recognizing that a healthy caregiver is essential to a healthy, happy autistic individual.

We cannot expect autistics and their families to survive and thrive if they are constantly at war just to get support.

Any one of us could reach the limit. Or anyone we’ve met. Nobody knows just how much someone can take, and what will be their breaking point. We need wholesale change in the way we support autistic individuals and their caregivers. The reality is if the caregiver is too stressed and is getting no help or relief, the whole family is in potential danger. These horrible stories will continue until something big changes.

Caregivers need to be heard and helped when they reach out. By the time a parent reaches the point of murder and suicide, it’s too late. Families need care and support from the very beginning, not just when things get rough.

Until then, keep your ears and shoulders available for your friends, in real life and on the internet (which is oftentimes who need it the most). Be a friend, be aware of what’s happening. Also, don’t hide your situation from the world. Open up to anyone you think will take you seriously.

And let your local government know how you feel about caregiver support and the lack thereof. Be loud, and be heard.

If the system can’t/won’t help us, we have to help ourselves.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read MoreExtreme Air Park – Hostility, Greed, and Autism

We in the autism community are, sadly, used to hearing about maligned special needs parents and children. It’s become an all-too-common topic in the news and blogs lately. While most of us know or are familiar with some affected persons, it’s rare (at least for me) to have a situation happen right in your own backyard.

Or down the street, in my case.

We live in Langley, British Columbia, just South of Vancouver. From what I’ve experienced in the almost four years we’ve lived here, it’s a really nice community. The people are kind, the schools are good, and children are welcomed almost everywhere. We have parks and playgrounds and activities for families on almost every corner. It’s not Utopia, but it’s a great place to raise a family.

As a child with autism, Jack is welcome with all other children. He has not been excluded from anything he has wanted to do, to our knowledge. He is gaining independence, but he does need accompaniment of his SEA for school activities, and a parent or caregiver for much of everything else.

Kelly Moonie and her son Kyle live in our community. Kyle, like Jack, has autism. I don’t know the Moonie family personally, but I hope their experiences here in Langley have been similar to ours. Most of them, that is.

Recently, Kelly took her son to the Extreme Air Park location here in Langley, an indoor gym of sorts featuring wall-to-wall (and up the wall) trampolines. We’ve been there ourselves, and can attest that it’s a lot of fun. For everyone. We even have a t-shirt.

Kyle was accompanied to EAP with his caregiver, who is charged with assisting him and ensuring his safety. Kellie was told she needed to pay the full price for the caregiver to enter.

Businesses that cater to children often admit a caregiver for free, or at least at a reduced price. Here in Canada, we have a program called Access 2 Entertainment, that addresses the issue directly.

From their website:

Launched in December of 2004, the Access 2 Entertainment program seeks to offer more opportunities for people with disabilities to participate in recreational activities with an attendant, without added financial burden. It is also designed to raise awareness and help businesses provide quality customer service to customers with disabilities.

It is vitally important that special needs children enjoy as much of a “normal” life as possible, and allowing caregivers to accompany them is a major part of that.

After their visit, Kellie sent an email to EAP, explaining this issue, and suggesting they change their policies. She received an email in return, assuring her there would be no such change.

Kellie answered the email, pressing them further on the issue.

The response she got was much less polite, and much more hostile.

From the CBC article telling their story:

“Our system is computerized. I am not lying to you. We know how many people are on the floor at any given time. But what would you know. C U next Tuesday,” replied (Michael Marti, on behalf of ) Extreme Air Park.

Yes, you read that right. C U next Tuesday.

With apologies for the vulgarity, C-U-N-T.

I don’t even know where to begin with this. Calling your customers names is never good business, but in the case of a special needs parent trying to enlighten you on a very important issue?

Firestorm.

Extreme Air Park is a bouncing wonderland, almost made for autistic kids. Maybe that’s the problem. They don’t want autistics. Perhaps I’m wrong, but that’s definitely the message they’re sending. By inhibiting equal access, the Extreme Air Parks are making it very clear that they don’t care for special needs individuals in their establishments. And if those persons wish to patronize the place anyway, they’ll pay for the privilege.

Charging a caregiver full price when they are only there to facilitate the individual who needs them – similar to a seeing-eye dog, if you will – is just plain greedy.

Special needs parents and autistics have enough struggles and obstacles in life already without ignorant businesses piling on.

Even if you do not have a special needs child, the way the company handled this is outrageous and beyond the pale. True, it may have simply been an unprofessional employee taking matters into their own hands, but when you’re speaking for an entire company, you should know better. I have no doubt that any parent attempting to communicate with EAP would have met with similar hostility and derision.

I could go on and on and rant and rave, but I won’t.

Instead, I’ll let you do it. Please.

Please take a moment to tell Extreme Air Parks how you feel about their policies, and the way they treated Kelly Moonie.

Below are the contact numbers for all of the Extreme Air Parks in Canada:

Richmond 604-244-5867

Langley 604-888-8616

Calgary 403-265-2733

Edmonton 780-479-7790

They are also on Twitter: @Extreme_AirPark

It would appear they’ve deactivated their Facebook account, but you can send them an email directly on their website here.

On behalf of Kelly and Kyle, Jack, the children of Langley, and special needs families everywhere, I urge you to take a stand.

I am.

But first, I’m going to go throw away that t-shirt.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read MoreAt The Heart of Darkness

I am a generally happy person. I try to find the humour and joy in everything, even when it would appear that there is none to be had.

It’s been difficult to find my smile lately.

I should elaborate. I have many reasons to smile daily, all day long. I have four amazing children, my beautiful, beautiful boys, whose every breath is reason to be joyous. I smile, but there is something lurking behind it. Something dark and sad, something I’m trying my best to understand.

I am anxious. I am depressed.

I have suffered from Post-Partum Depression (PPD) after each of my children’s births, in increasing severity. My youngest son was born in October and this time it came over me like a tidal wave, the worst yet. Many people and medications support me, but the dark cloud persists. I feel like I’m going through the motions, watching my happy life from the outside.

I’m trying to put my finger on it. Baby blues? Could still be, my child is only six months old. Four children seven years and younger? Of course. There is stress in wrangling them here and there, getting them into bed, entertaining them, feeding them. They eat a lot. Seriously, a lot. But all of those things are part and parcel with motherhood. All of those things are expected. If I didn’t think I could handle this job, I wouldn’t have applied, and kept applying. My entire life brought me to this point, and I wouldn’t change a thing.

(Ok, in a perfect world there are things in my past I would have done a whole lot different, but we don’t get do-overs. It’s easier to accept that the decisions I’ve made in life, for good or bad, have created my life today. And I kind of love my life today.)

Autism? Autism is a huge part of our lives. It’s pervasive, and up to now, we’ve made it work. I realize, however, that things are changing. It’s getting more difficult. Jack is getting older. He’s getting stronger and smarter. A lot smarter. And he’s busting through all of the tools I’ve used to help him – and myself – cope. So we’re at a plateau of sorts. Or maybe diverging paths. Jack is heading into his future, and I am scrambling, trying to keep up with him. Trying to get us back in sync.

I’m flailing.

Another entity has also invited itself into our family, or is trying to. ADHD*. We are having one of our sons assessed, and I’ll be surprised if that’s not the outcome. It’ll be a few more months and a few more doctor’s appointments and a few more assessments until we know for certain, but I want to know for certain. I don’t like ambiguity, especially in my home, with my children. I am staring down the barrel of this the same way I did with autism. If my child has a challenge, I want to know what it is so we can get going. Get a handle on it. Get ahead of it. Early intervention is the best solution in any situation involving a child. Involving anyone, honestly.

If that were the only issue, I would be fine. But no, ADHD didn’t want to stop there. In the process of understanding what’s happening with my son, I started realizing something about myself. The doctor we saw last week asked me something that threw me for a loop. After going over our family’s medical history, she asked a simple question. One I hadn’t ever heard put in quite this manner.

“Does his behaviour resemble anyone in your family?”

I looked at her, stunned. The sky opened up, the clouds parted, a window of clarity descended upon me.

Or maybe I blinked.

Yes, in fact, it did resemble someone in my family.

Me.

Insert montage of snapshots of my life: my elementary school report cards describing in detail how I couldn’t sit still, talked too much, couldn’t focus; a trip to the doctor as a small child, with the word “hyperkinesis” ringing in my mind; family members telling me I talked too much, sit still, calm down. I was obsessed with candy (the bad kind, not the kind I give my kids now). I stole money from my mother’s wallet and my father’s bureau. I couldn’t handle not getting what I wanted, and screamed and banged my head when I couldn’t deal. Punishments didn’t mean a lot to me, as I was somehow always able to adapt. I lived in constant anxiety about one thing or another. My main recollection of myself as a child? Obnoxious.

That is how I always thought of myself, until one day in high school I looked in the mirror and decided I wasn’t going to be that person anymore. I embarked on a long journey of figuring it all out. Teaching myself how to take turns in conversations and not only talk about me and mine. Working to tune out the sensory overloads that hurt my head. Putting myself into social situations and act accordingly, even though I was deathly afraid. Trying, desperately, to become a “me” I could look in the mirror and love.

That’s a lot to carry around.

I pulled out those report cards not too long ago, and read them all in detail. And I cried. I cried for the little girl who never really understood why she was in trouble. Who didn’t know why she did the things she did, but couldn’t stop herself from doing them again. Who desperately wanted to fit in somewhere, anywhere, but just… couldn’t.

And I cried for my children. Because I don’t want them to ever feel what I felt. I want to shelter them from the awkwardness, the self-consciousness, the underlying feeling that they don’t belong.

I want my sons to know what is within them that makes them do things differently sometimes, and to understand not only how to manage and cope, but to know and believe that they are perfect exactly the way they were born.**

I’m not under the illusion that I can save my children every heartbreak, every hurt. Part of growing up is experiencing the things that will make them into strong men, whole men. Heartbreak and hurt are a part of the deal as much as love and fulfillment. Yin and yang.

If I can do anything to keep my children from feeling the confusion I had, I will. If I can tell them every single day that they are beautiful and confident and awesome just the way they are, they might believe it. I can try. I have to try.

In the moment when the doctor asked that simple question, I realized that my child is very much like me. He’s the only one of our four boys who really looks like me (the other three are clones of my husband), and now I know he shares more than my features.

The most important thing I took out of that meeting was the very real possibility that if my son has ADHD, I most likely have it, too. It’s genetic, so it’s entirely possible. The most damning evidence, though, is that word I remember so vividly from long ago. Hyperkinesis. I’ve known it all of my life, but never really understood what it meant for me. I know now that hyperkinesis is what they called ADHD before it was ADHD.

I know that after my mother took me to the doctor and we learned that word, she put me on the Feingold Diet and cut out all artificial colours and flavours. I don’t remember anything else, though. No medications, no more doctor’s visits. No more addressing the elephant in the room.

Me.

Sadly, my mother has passed away, so I can’t ask her all the questions that are running around in my brain. My father has told me as much as he recalls, but there’s more. I’ve been questioning myself since Jack was diagnosed almost five years ago, and now it all seems to be making sense.

I want to know more. What can I do to get more focus? Would medication help? Is the medication I’m on making it worse? I want to banish the ambiguity.

So, I think I’ve discovered the source of the darkness: I am overwhelmed. I have several very large balls in the air, and I’m afraid if I drop them, I’ll fail my family. Autism. ADHD in my child. ADHD in myself. The anxiety. The unknown.

I am strong, I have been through worse. I just want answers, and I want clarity.

I want to help my son navigate his life with autism.

I want to help my other son cope with whatever is challenging him.

I want to get ahold of myself so I can live my life free of this weight that’s pressing me down.

I want to smile.

*****************************************************************

*There are some who may hear ADHD and think, “Oh, that’s not so bad, it’s not as bad as autism.” No, it isn’t, it’s different. It’s still a challenge, both to the individual who has it and the family that supports them. It’s work, on top of lots of other work. Not impossible, but difficult nontheless.

**I feel it’s important to note that I do not blame my parents in any way for the way I felt, or the way they handled me. This was forty years ago, and an entirely different world. If anything, my experiences have informed me well to guide my own children.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read More