Be The Village

Autism parents. Autistic adults.

Two communities that have the same essential goals, but are rarely able to meet on common ground.

One point of contention is the internet, and how autistic people are portrayed.

The latest flame on that fire is a video by Kate Swenson of Finding Cooper’s Voice, wherein she talks about her son Cooper’s nonverbal autism.

Kate’s website, Finding Cooper’s Voice, rose in visibility last year, when her video about an altercation at a special needs playground went viral. Then, in October, Kate and Cooper’s video submission to Jimmy Fallon and Today’s “Everything is Mama” contest took the top prize.

Kate makes a lot of videos about her family, and Cooper, in particular.

Kate’s latest video

This latest video, posted via Today.com, as caught a lot of attention, both good and bad. Parents of nonverbal children understand and sympathize, and a lot of autistic people are very, very upset.

The main concerns I’ve seen are that the video is “ableist,” “exploitative,” and essentially a Mommy Blog pity party.

And they’re right, to a point.

People have been arguing since the invention of the internet whether or not posting videos/photos of their children is acceptable. Some think it’s absolutely abhorrent, while others embrace the platform with abandon.

There is a lot of concern about Cooper’s right to privacy, and future humiliation he may suffer because of his mother’s posts and videos. I, myself, have faced similar scrutiny, particularly when I started this site, eight years ago. I take care not to post anything that disrespects or would embarrass my children, and from what I’ve seen of Kate’s work, she does the same.

My opinion. Yours may vary.

I think the situation here is a little more serious than whether or not Kate is indulging in self-pity at Cooper’s expense.

This is also about more than Cooper’s right to privacy.

This is about his life.

People like to say that special needs parents are “picked” for their children, or that “God never gives them more than they can handle.”

Those are nice tropes, but in reality, parents of special needs children are no different or better or more special than any other parent. Every parent wants the best for their child, and sometimes that journey is a lot harder and full of stress.

A kind of stress you can’t explain to someone not in it.

Even another autistic person.

I am autistic, and I am also a parent. A parent with four children, three of whom have special diagnoses, two of whom are on the spectrum, too.

I understand that to an autistic person, hearing a parent say “horrible things” about their autistic child is “ableist” and offensive.

I also understand, as a parent to autistic children, that hearing a parent describe their reality is hard to hear, but necessary.

This is a cry for help. For her, for her child.

Instead of vilifying her, let’s recognize that and be her village.

Kelly Stapleton was an integral part of the autism blogosphere. She was a bright and shining light, while simultaneously sharing her struggles with her daughter Izzy.

Her life was hard. Really, really hard. And when Kelli thought she had nowhere left to turn, and nobody left to help her family, she made a desperate decision that changed her family’s lives forever.

She tried to kill Izzy, and herself.

Kelli and Izzy

Kelli got to the point where that action seemed like a logical ending to their pain. To her pain.

I am in no way condoning her actions. Not at all.

However, I think we need to learn from them. There has been an epidemic of caregivers taking the lives of their autistic children/wards, most because they can’t find a way out of their world.

The autism world can be one of utter isolation. Family and friends back off; total strangers judge silently.

As autistic adults, we purport to want the very best for our fellow autistics of all ages. It’s time to put some walk to that talk. It’s time to reach across the table with an olive branch and a life jacket.

We simply cannot have it both ways. If we do not reach out and support parents who are desperate and in pain, they may break. Supporting these parents, instead of ridiculing and criticizing them, IS supporting autistic people.

How can we possibly insist on putting the health and welfare of autistic people first, if we are not willing to help their caregivers?

We know best. We are their children, grown up. We know what our parents went through, and it wasn’t always easy. Would you have wished them to suffer in silence, or to reach out for a hand to hold or shoulder to cry on or simply a sympathetic ear?

We can do better. For Cooper. For Izzy. For every autistic child. They need our village.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read MoreAutism in British Columbia: Crisis in Process

My son Jack was born in the United States and raised in Los Angeles until the age of four and a half. Just before he turned two, he entered the California Early Start program for children with a risk of developmental delay or disability. We called for an appointment in August of 2o06, and by the end of September of the same year, he was enrolled in a variety of interventions and therapies.

At age three, he was formally assessed and diagnosed with autism by both the Lanterman Regional Center and the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). He was transferred to autism-specific supports, where he remained until we moved.

From the time Jack was twenty-two months until he was four and a half, Jack received the following interventions and therapies:

AGE TWO

- Collaborative preschool with typical peers in a clinic-based classroom, three-to-four days a week

- Two hours a week of clinic-based Occupational Therapy

- Two hours a week of home-based Speech Therapy

- Several sessions of Feeding Therapy

- He was also offered full-time preschool, additional Occupational Therapy, Floortime Therapy, and Respite Care, which we did not feel were necessary at the time.

AGE THREE to FOUR

Provided by LAUSD:

- Individualized Education Program (IEP) support

- Collaborative preschool with typical peers in a public school classroom, five days a week

- Full-time Behavioural Intervention Implementation (BII) aide at school

- Two half-hours a week of school-based Speech Therapy

- Two half-hours a week of school-based Occupational Therapy

Provided by Lanterman Regional Centre:

- One hour a week of clinic-based Occupational Therapy

- Twelve hours a week of home-based Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA)

- Respite Care

- Parent training workshops

We also supplemented his therapies at home, with strategies learned from his providers.

Several of the supports at school and at home were coordinated through the same non-profit organization, so there was continuity in both areas. We felt very confident that our son was receiving every support he needed, and that should he need more, the options were available to us.

We were given choices of providers and schedules, and the ability to change supports and therapies as we saw fit, but we were guided through the process by a social worker at Lanterman (Early Start), and then a caseworker at Lanterman, a support worker at LAUSD, and a coordinator at the non-profit who provided our BII and ABA aides.

It is important to note a couple of things. First, we never saw a bill. Not once. My husband and I signed authorization forms, reports, and time cards, but we were never financially responsible for anything.

Secondly, we were given suggestions and options as to what Jack needed, according to several observations and reports. We were able to give our input, but we were not responsible for creating his treatment plans. We never felt like the burden of figuring out what he required was on us.

Finally, we never saw a pediatrician or medical doctor (other than the diagnosing psychiatrists) for Jack’s autism. In fact, it came as a bit of a surprise to his pediatricians when we told them about his diagnosis. Jack has never had any of the health issues commonly associated with autism, and as it is not required in California, we had no reason to include his doctors in the diagnosing process.

When our family moved to Canada, Jack was in the process of transitioning from preschool to Kindergarten. In Los Angeles, he would have had full-time BII support, and continued with both speech therapy and home-based ABA (he had graduated from clinic-based occupational therapy) for as long as necessary.

I cannot speak to how his support would have waxed or waned over the school years, but I have only good things to say about our experiences up to that point.

I can, however, tell you what happens here in British Columbia.

Once we were settled, we were required to get Jack a new autism diagnosis from a Canadian doctor in order to qualify for provincial autism funding. Government funding is Canada’s answer to autism support, similar to the Regional Center system in California.

First, we had to see a pediatrician, and convince him Jack needed a referral for diagnosis. I was honestly shocked when he balked at giving it to us, even though Jack had already been formally diagnosed in the United States. Twice. The doctor wanted to rule out ADHD (which, it turns out, Jack does have), and Fragile X Syndrome (which he does not), before he would even consider referral. I pushed, though, and he relented.

Next came The Wait. We were told the wait time for assessment would be almost two years, and indeed it was fourteen months before he was seen.

Fourteen months is forever in the life of an autistic child and their family.

It can also be the difference between full- and no-support.

Children assessed with a spectrum disorder in BC under the age of six receive $22,000 a year of funding to pay for their various supports. The family is responsible for deciding which therapies and interventions are necessary, and all of the hows and whens and whos of making them happen. I know how overwhelmed we were in Los Angeles, and we had several agencies overseeing and coordinating everything for us.

Many families in BC are lost and confused as to what is necessary and when, and who to trust to give them good advice. They are expected to become autism experts overnight, and to know what their child needs at any given time.

Once a child on the spectrum reaches age six, the yearly funding drops to a mere $6,000. To cover every single thing the child or young adult needs.

$6,000 doesn’t go very far, in case you’re wondering.

Now consider the child who has been waitlisted until they are six or seven, eight, or older. Those children don’t get retroactive funding; they’re given the same $6,000 every other child over six gets.

$6,000 to sink or swim.

My husband and I often wonder where Jack would be in his development if he hadn’t had such intensive interventions and instead had to wait years to be seen. The difference between the two months it took in Los Angeles and the fourteen months it took in British Columbia is monumental.

It’s a lifetime.

In the first fourteen months of Jack’s therapies, he learned to use his upper body. He learned how to play.

He learned how to talk.

I cannot stress enough how important the first year of Jack’s interventions was in shaping the person he is today. That time was invaluable to him, and to us.

I have met many families of autistic individuals here in BC and have heard a lot of stories. Some wonderful, many concerning. Some downright terrible.

In the Lower Mainland, where we live, there is only one team that assesses and diagnoses autism. One team for a large and rapidly growing population – the fastest growing region in Canada.

Wait times to be seen are so outrageous, families who are financially able resort to paying for their own assessments out of pocket. Even those clinics now have tremendous wait times.

Yes, there are legitimate circumstances where a child may be older before he or she is diagnosed, but for families seeking help for younger children, the situation here can be bleak.

I cannot imagine where Jack would be today without the solid start he got at a very young age.

I cannot imagine the kind of support he would have gotten if we had to decide his plan of action alone, without professional guidance.

I cannot imagine the outcome if we had had serious budget restraints, or had to turn down therapies because we simply could not afford them.

Autistic children in Alberta get up to $60,000 a year for supports through age 18. Why should children in British Columbia not get the same?

Why do children over the age of six get so much less than younger children? Is autism less severe over the age of six?

Why are families left to fend for themselves in a province so well known for caring for its citizens?

It breaks my heart to see even one child go without the therapy and intervention he or she desperately needs. I don’t understand how a province can willingly stifle the potential of certain individuals because of their age or where they live.

It’s just not right.

It’s not Canadian.

It needs to change.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read MoreExtreme Air Park – Hostility, Greed, and Autism

We in the autism community are, sadly, used to hearing about maligned special needs parents and children. It’s become an all-too-common topic in the news and blogs lately. While most of us know or are familiar with some affected persons, it’s rare (at least for me) to have a situation happen right in your own backyard.

Or down the street, in my case.

We live in Langley, British Columbia, just South of Vancouver. From what I’ve experienced in the almost four years we’ve lived here, it’s a really nice community. The people are kind, the schools are good, and children are welcomed almost everywhere. We have parks and playgrounds and activities for families on almost every corner. It’s not Utopia, but it’s a great place to raise a family.

As a child with autism, Jack is welcome with all other children. He has not been excluded from anything he has wanted to do, to our knowledge. He is gaining independence, but he does need accompaniment of his SEA for school activities, and a parent or caregiver for much of everything else.

Kelly Moonie and her son Kyle live in our community. Kyle, like Jack, has autism. I don’t know the Moonie family personally, but I hope their experiences here in Langley have been similar to ours. Most of them, that is.

Recently, Kelly took her son to the Extreme Air Park location here in Langley, an indoor gym of sorts featuring wall-to-wall (and up the wall) trampolines. We’ve been there ourselves, and can attest that it’s a lot of fun. For everyone. We even have a t-shirt.

Kyle was accompanied to EAP with his caregiver, who is charged with assisting him and ensuring his safety. Kellie was told she needed to pay the full price for the caregiver to enter.

Businesses that cater to children often admit a caregiver for free, or at least at a reduced price. Here in Canada, we have a program called Access 2 Entertainment, that addresses the issue directly.

From their website:

Launched in December of 2004, the Access 2 Entertainment program seeks to offer more opportunities for people with disabilities to participate in recreational activities with an attendant, without added financial burden. It is also designed to raise awareness and help businesses provide quality customer service to customers with disabilities.

It is vitally important that special needs children enjoy as much of a “normal” life as possible, and allowing caregivers to accompany them is a major part of that.

After their visit, Kellie sent an email to EAP, explaining this issue, and suggesting they change their policies. She received an email in return, assuring her there would be no such change.

Kellie answered the email, pressing them further on the issue.

The response she got was much less polite, and much more hostile.

From the CBC article telling their story:

“Our system is computerized. I am not lying to you. We know how many people are on the floor at any given time. But what would you know. C U next Tuesday,” replied (Michael Marti, on behalf of ) Extreme Air Park.

Yes, you read that right. C U next Tuesday.

With apologies for the vulgarity, C-U-N-T.

I don’t even know where to begin with this. Calling your customers names is never good business, but in the case of a special needs parent trying to enlighten you on a very important issue?

Firestorm.

Extreme Air Park is a bouncing wonderland, almost made for autistic kids. Maybe that’s the problem. They don’t want autistics. Perhaps I’m wrong, but that’s definitely the message they’re sending. By inhibiting equal access, the Extreme Air Parks are making it very clear that they don’t care for special needs individuals in their establishments. And if those persons wish to patronize the place anyway, they’ll pay for the privilege.

Charging a caregiver full price when they are only there to facilitate the individual who needs them – similar to a seeing-eye dog, if you will – is just plain greedy.

Special needs parents and autistics have enough struggles and obstacles in life already without ignorant businesses piling on.

Even if you do not have a special needs child, the way the company handled this is outrageous and beyond the pale. True, it may have simply been an unprofessional employee taking matters into their own hands, but when you’re speaking for an entire company, you should know better. I have no doubt that any parent attempting to communicate with EAP would have met with similar hostility and derision.

I could go on and on and rant and rave, but I won’t.

Instead, I’ll let you do it. Please.

Please take a moment to tell Extreme Air Parks how you feel about their policies, and the way they treated Kelly Moonie.

Below are the contact numbers for all of the Extreme Air Parks in Canada:

Richmond 604-244-5867

Langley 604-888-8616

Calgary 403-265-2733

Edmonton 780-479-7790

They are also on Twitter: @Extreme_AirPark

It would appear they’ve deactivated their Facebook account, but you can send them an email directly on their website here.

On behalf of Kelly and Kyle, Jack, the children of Langley, and special needs families everywhere, I urge you to take a stand.

I am.

But first, I’m going to go throw away that t-shirt.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read MoreGuess What? I Have Autism!

“Hi! I’m Jack. I have autism.”

A sentence I wasn’t sure I was ready to hear. Yet, so pleased to see it exclaimed loudly and proudly.

Two weeks ago my husband David and I told Jack he has autism for the very first time. We’ve never hidden anything from him, we just wanted to wait until we were certain he’d be able to understand the gravity of it all to address it directly.

We discussed it for months in advance, tried to plan out what we wanted to say. And what we didn’t want to say. We decided to wait until the summer, so he would have time to adjust to his new reality unfettered by school stresses. We looked at books, we asked what others had told their children.

Summer came and we still waited. For the right time, the right place, the right… whatever. We finally decided to take him out to lunch alone, where we could have a conversation without his brothers drawing focus. It would be perfect.

And we all know the best laid plans always go according to, well, plan.

The days passed and still no discussion, no lunch date. Then one day we were all sitting around the kitchen table doing arts and crafts and what-have-you. I looked at David, he looked at me and shrugged. It just seemed like a good time.

“Jack, do you know what autism is?”

He wasn’t sure, so we expanded on some things he already knew: people have different likes and dislikes, people don’t all look the same, people think differently.

That’s been a recurring theme in our family for years. Whenever one of the children asks why someone is a certain way, or why somebody likes something they don’t, or any time something is not the same as what they know, we say it.

“People’s lives are different.”

We knew someday Jack (or his brothers) would realize that he’s not like most of the other kids, and we wanted him to know that different is not wrong. It’s not strange. It’s not weird or funny or less than. Different is just different.

We described the spectrum, and how all people who have autism fit somewhere on it, but are not the same. That even within the autism community there are differences, and that’s OK.

We told him that autism is why sometimes sounds are too loud and lights are too bright and the Titan AE theme song drives him nuts (although to be fair, it’s really annoying). Autism is why he has a helper at school, and why he needs to run around in the halls periodically. It’s why he takes melatonin to sleep at night.

It’s also why he wants to know everything about every subject that interests him, and wants to share it all with anyone within earshot. It’s not why he’s curious, but it’s probably why he’s curiouser.

So when we said the words “you have autism” to Jack, and explained what we meant, he wasn’t upset. He wasn’t scared or troubled in any way. He was quite the opposite.

I’m pretty certain Jack believes he has some sort of super powers.

Which, of course, he does. Duh.

So, without further ado, Jack’s thoughts on autism.

On the concept of a spectrum, and where he falls on it (we told him he started in the middle, and now he’s toward the high-functioning end):

“It’s hard to read if you’re in the middle of the spectrum. You just have to show your parents the words.”

“If you’re way past schedule on learning, nothing will stop you from learning again and again and again to get to the other end of the spectrum.”

Jack does understand that not everyone can move from one end to the other, although his main concern about those individuals is that they may not be able to have sex properly to have children. He’s quite interested in the mechanics of having babies at the moment.

I’m certain he’ll have more to say on the non-sex aspect at a later date.

On the fact that he was born prematurely, and how that may have contributed to his autism (his correlation, not ours):

“If you’re early (premature) you have a lot more time to learn. If you’re past schedule (post-dates, like his brothers), you don’t have as much time to learn.”

So, according to Jack, he’s got one up on his brothers because he was born six weeks premature.

On early intervention (he started services when he was 23 months old), and the important role parents have in the therapy process:

“You (parents) helped me learn. You also brought someone else over to help teach me to learn.”

“It’s all because of my parents that other people came and taught me. So parents do help out with learning, not just school and other classes. Mostly parents. But mostly school.”

Um, thanks?

“And you learn mostly everything at university.”

OK then.

Some random thoughts on autism:

“I couldn’t walk when I was born, and it’s because of the spectrum.”

Hm, probably not the case.

“I know how to read, so I’m really good at autism.”

I guess so?

We finished up by asking him how he felt now that he knows about autism. Turns out, he thinks it’s pretty cool.

“I think that having autism is great. Of course, what do you know?”

Not much, apparently.

“Do you like autism a lot?”

Yes, yes I do, in fact.

“Well, thank you!”

You’re quite welcome, little man, it’s been my pleasure.

When his aunt and cousins came over later in the day, he ran up to them and gleefully exclaimed, “guess what?!? I have autism!”

Let the celebrations begin.

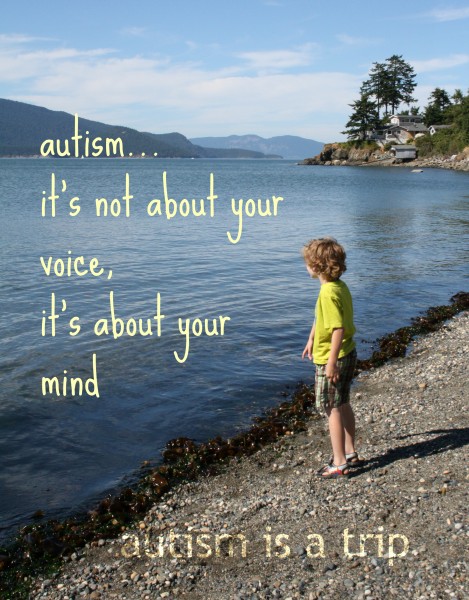

And, as is his wont, Jack summed up autism in the most eloquent way possible. From the mouths of babes and all, words of wisdom:

“I think it (autism) helps me want to do lots of things. It’s great for the mind, because it can help you do lots of things.”

And finally:

“Some people (with autism) can’t talk – it’s not about your voice, it’s about your mind.”

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

***********************************************************

Next up in this series – what Jack’s brothers have to say about autism.

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read More

Dear Jack… You Have Autism.

Dear Jack,

There is something your Daddy and I have wanted to tell you for a long time. Something that we weren’t sure how to bring up, or when. Something that has the potential to change the way you live your life.

Jack, you have autism.

You are my firstborn son, my love, my everything. I have adored you since long before I knew you. I waited to meet you my entire life, and when I met your Daddy, he was just as excited. We knew from the very first time we saw you on the ultrasound monitor that your name would be Jack. We didn’t even think twice, we just knew immediately, right there and then. Jack.

You know that you came into this world a bit early, earlier than your brothers. I spent a long time in the hospital waiting for you, waiting for the day it would be ok for you to come earthside. You were early, but very healthy. Daddy and I held you and couldn’t believe how beautiful you were. You are. Perfect little nose, perfect blonde hair, perfect little fingers and toes.

Perfect.

You came home and made us a family. You are the first, the oldest. Your three younger brothers love you, learn from you, and adore you.

We have known you have autism since you were three years old. Actually, that’s when the doctors told us officially. We’ve known you were special since before you turned two. You couldn’t speak, but you knew things. You were incredibly smart. I have no doubt you understood everything.

Knowing you have autism didn’t really change a lot for us. If anything, it made everything easier. You were able to get the support you needed, and some amazing people came into our lives because of it. Miss Amanda helped you learn how to talk and play. Aki and Jane helped you learn how to climb and swing and do small puzzles. Miss Amelia, Miss Deborah, Miss Shelby and Miss Jesse gently guided you into school, with lots of love and joy for learning. And Miss Shirin, who made sure that someone was always at your side (Eric, Charlie, Geoff, and Christine), teaching you how to cope when things get to be too much, how to focus your attention when necessary, how to be safe, and how to explore and enjoy the world around you with freedom.

They all gave you what every child wants and needs. Freedom.

When we moved to Canada, you started “real” school. Kindergarten. Grade One. Grade Two. This fall you’ll be going into Grade Three, which I can barely believe. Not only are you thriving educationally, you’re speaking French while you do it. Even more amazing people have guided you to this point: Mme Riel, Mme MacIntyre, Mme Dowes, and Mme Okeyere have taught you as they taught every other child in their classes, and gave you every respect and inspiration you deserve. Mr. Yaniv and Mr. Perk have guided you from behind the scenes, putting you on the right path and making certain everyone charged with your care is trained properly and know how to support you in the best way possible. And Mme W in Kindergarten, and Mme S ever since, have been by your side every single day.

Because of this team of professionals, this group of people who both want you to succeed and love you dearly, you are the boy who stands before me today. Jacktor The Tractor. JackJack. Jack.

A child who once could not speak at all, who now can not only speak English on a high school level, but can speak French as well.

A child who had such low upper body tone as a toddler that he could barely climb a play structure, who has now mastered not only the monkey bars, but also taught himself how to ride a bicycle (without training wheels).

A child who had no concept of how to play with his toys or colour or use his imagination, yet has now filled my home with extensive drawings of whatever the popular subject is this week, expansive and intricate art projects he’s built, and fantastic books he’s written about wild adventures and alternate universes.

Autism is not a bad thing, it’s just a thing.

Autism is why you only had four words when most other kids your age were chatting away. Autism is the reason you don’t like fireworks, or big crowds of people. Autism is why you get to walk around in the halls at school when being in class just gets to be too much.

It’s why you run through the house in loops, and don’t always listen when someone is talking to you. It’s why I ask you to look into my eyes, so I know for sure that you’re hearing me. It’s why the loud things and the buzzing things and the light things and the random things make you stressed a lot more than other people.

Autism is why you always went to special gyms and preschools and your brothers didn’t. It’s why we went into Vancouver so many times to see the doctors at the place with all of the toys, even though you weren’t sure exactly why we were there.

But Jack, there is something incredibly important for you to understand about all of this. Autism is the reason for a lot of stress in your life, but it is also responsible for you being “you.”

Autism is the reason you could write your name and build intricate structures at a very young age. Autism is the reason you were able to learn how to read in English, how to ride a bike, how to tie your own shoes, and any number of other tasks you took it upon yourself to learn. To teach yourself.

Autism is why you see things a little bit differently than your brothers. And your friends. And most people, for that matter. People look at things and see them for what they are on the surface, you want to know what’s inside. You yearn to dissect and examine everything that interests you, and a whole lot of things interest you.

It’s the reason your younger brothers can read, write, do math, name all of the planets and discuss weather anomalies and scientific principles far beyond their years. Because you have taught them. Because you are curious and thirst for knowledge, and want to share it.

Because you have autism.

And that’s why we’ve waited. We don’t want you to change anything. Not the way you live, the way you think, the way you see the world. Nothing has changed for us, and nothing should change for you.

I know now you will want to know every single thing there is to know about autism, because that’s what you do. In your investigations, you are bound to read some not-so-positive things about autism, about the autism spectrum. There are people out there who believe that autism comes from lots of different sources, that believe people with autism need to be “cured,” that want to eradicate autism completely.

You will make up your own mind about all of these things as you grow and experience life as a person with autism. Our job as your parents is to love and support you on your journey to adulthood, just like your brothers. We have given, and will continue to give you, every advantage we can to make it as stress-free as possible.

Sometimes, though, the stress with break through. You may get frustrated with other people, difficult situations, and even yourself. But I need you to understand the most important thing of all.

You are special. You are Jack. You are not autism.

Autism is not who you are, or what you are. Autism is just another part of you, like your thick, curly hair, your long legs, and your blue eyes. Autism did not determine your personality, and it cannot determine your limits. Only you can decide those things. You have the power to be whomever you want in this world, and whatever kind of person you’d like to be.

My wish for you is that you remain loving and curious. That you have the tools you need to cope when things get difficult, and not let the difficulties stop you. Please don’t ever stop learning.

Jack, I want you to show the world that you don’t live in spite of autism, or because of it. You are amazing because you are Jack.

With all of the love in the world,

Mama

Share this: Twitter | StumbleUpon | Facebook | digg | reddit | eMail Read More